BRIDGEWATER, Va. – The first tune begins with a fiddle reel, and feet start to shuffle in time. A caller’s voice rises above the music, “Balance and swing!” Pairs spin down a line of smiling strangers. Laughter echoes through the hall, punctuated by the scrape of sneakers on a wooden floor. For newcomers, it looks choreographed, almost rehearsed. But this is no performance; it is a community in motion.

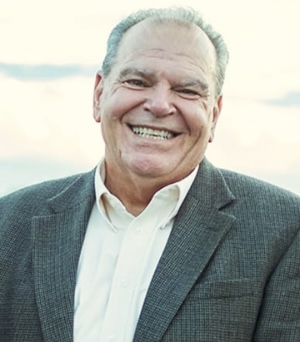

Among the dancers is Wayland Moore, 81, who moves with the quiet confidence of someone who has learned that motion itself can be medicine.

“My oncologist told me to keep dancing,” he said. “So I did.”

Moore, a retired engineer and quality management consultant who later founded WayMooreHealth.org, found contra dancing decades ago, long before it became a metaphor for his own survival. His website chronicles a deeply personal journey through two cancer diagnoses and recovery, blending research on stress physiology with reflections on joy and purpose. He shares it through ways such as what he calls “the dance button,” a small wearable name tag pinned to the shirt of dancers.

The button reads, “I CONTRADANCE — FOR HEALTH AND FUN”, explaining how his passion for movement and community became central to his healing. His philosophy is simple but profound: sustained movement, connection, and music can activate the body’s “blue zone,” a state of rest and restoration.

“Chronic stress breaks down the body,” he said. “But dance rebuilds it, not just physically, but emotionally.”

On his website, Moore outlines how constant stress responses, such as the “fight, flight, freeze, and fawn” patterns, can wear down immune resilience. Dancing, he argues, does the opposite. It interrupts those stress cycles, strengthens social ties and nurtures what he calls ikigai, a Japanese term for life’s purpose.

At the heart of that philosophy is contra dancing, a centuries-old folk form that is equal parts physical exercise and social ritual.

A tradition that moves people literally

According to the Country Dance and Song Society (CDSS), contra dancing evolved from English and French “longways” dances, where couples face each other in two lines. Dancers move through repeating figures like swings, do-si-dos, and stars, guided by a live band and a caller. Every few minutes, partners change, so by the end of a single dance, nearly everyone has connected in motion.

Each set lasts about ten minutes, but the night can stretch for hours. Between tunes, dancers catch their breath, exchange smiles, and return to the floor. There is no competition or judgment, just rhythm and laughter. As dancer Pamela Patrick puts it, “It’s just fun.”

Patrick began contra dancing in the early 1990s and spent a decade organizing events in Staunton and at Mary Baldwin before stepping back to focus on dancing itself.

“I first came for the exercise,” Patrick said. “But I stayed for the people.”

Her tone softens when she recalls the early days, when finding enough dancers for a full set felt like a victory.

“It’s not about performance,” she said. “It’s about connection, that moment when you’re in sync with everyone else in the room.”

For Patrick, contra dancing has become a lasting part of her life because of the community that surrounds it. She describes the dances as friendly and relaxed, explaining that newcomers quickly find help from others on the floor.

“People help each other,” she said. “If you mess up, no one cares.”

A community rebuilt on joy and inclusion

That sense of unity is what kept Michele Clark, the Shenandoah Valley Contra Dance coordinator, organizing events month after month.

“We all just sort of know everybody” she said. “I went to England to Contra Dance and knew people from Virginia!”

Clark began dancing a decade ago and was a board member when the pandemic forced events to pause. Restarting, she said, “wasn’t easy.” Attendance had dipped and many longtime dancers were hesitant to return. But slowly, the sound of fiddles returned to the community halls.

“Now we’re rebuilding,” Clark said. “People travel from all over Harrisonburg and Charlottesville.”

Part of that renewal has involved making the community more inclusive. Clark notes that many groups now use larks and robins instead of the traditional gendered terms gents and ladies, allowing anyone to dance either role.

“It’s simple,” she said. “If you can walk, you can contra dance!”

That openness has drawn a younger, more diverse crowd, including college students, teachers, and retirees, all drawn by the same appeal: belonging through movement.

From the floor to the soul

To an outsider, a contra dance might seem repetitive. But dancers know that the magic lies in the pattern itself, a shared rhythm that demands presence but not perfection.

“You don’t need to be graceful,” Patrick said with a laugh. “You just need to show up.”

For Moore, showing up became a form of therapy. During chemotherapy, he describes feeling his strength ebb away. But at each dance, he found a reason to push forward, a reason to believe his body still worked.

“When you move, you tell your body you’re alive,” he said. “That message matters.”

His online writing extends that lesson to others facing illness or burnout. In Two Cancers, Two Stories, Moore reflects on how movement and gratitude supported his recovery. He said that staying active helped him feel alive during treatment and that dancing reminded him his body was still working.

At a recent dance in Verona, that philosophy played out vividly. A teenage girl guided her grandmother through the steps; a couple laughed as they missed a turn; and at the center, Moore and Clark shared a brief swing, smiling as the music lifted.

The science of connection

While Moore’s background is personal, his ideas echo research on movement and social well-being. Studies on folk dance link it to lower rates of depression and stronger social cohesion, especially among older adults. CDSS notes that contra dancing’s built-in partner changes create instant inclusivity: “By the end of a dance, everyone has danced with everyone.”

That shared rhythm seems to activate something deeper than muscle memory, a reminder that humans are wired for connection. Patrick sees it every night.

“Even when people walk in alone, they don’t stay that way,” she said.

Clark agrees, noting how the mix of ages and experiences keeps the dance vibrant.

“We’re seeing new faces,” she said. “Younger dancers, older dancers, people who just want to move and connect.”

The final swing

By the end of the evening, the music fades and dancers begin to gather their things, still laughing and talking. Moore watches the room with a quiet smile.

“You don’t heal alone,” he says.

In that moment, contra dancing becomes more than steps. It is an act of defiance against isolation, stress, and stillness. It is the embodiment of Moore’s mantra: movement as medicine, joy as resilience.

As the lights dim and the last waltz begins, dancers call out softly, “One more dance!” Couples line up again, hands clasped.

It is a simple gesture, but in a world where people crave connection, it is everything.