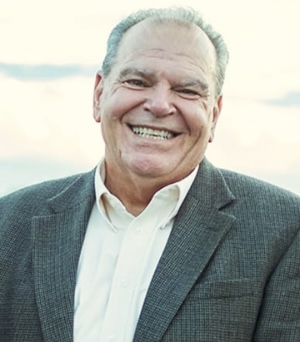

BRIDGEWATER, Va. – It started with being a ball boy at his father’s practices.

Dustin Green, now the defensive pass game coordinator and defensive back coach at Bridgewater College, started playing football when he arrived in high school.

Sure enough, over the years, he stayed with the game and was fortunate enough to play it at the collegiate level.

“The coaching and playing football came from my dad,” Green, now 26, said. “My parents have always supported me and put me in competitive environments.”

Not too long after playing his last college career game, he decided he couldn’t walk away from the sport.

Now, in 2025, he’s coaching it at his alma mater after playing defensive back for the Bridgewater Eagles for five years.

Building a coaching identity

Green said he didn’t start thinking about becoming a coach until the summer after his playing career ended and earned his master’s degree in Human Resources from Bridgewater College.

“Once my career ended, I realized how much I miss competition,” Green said.

Now in his fourth season as a coach, he says he relies on his experience from playing the game to help his players better understand schemes and play calls. Green said the biggest challenge he faced in making the shift from playing to coaching was remembering that he is not just managing himself now.

“You can’t know only one position, you have to know the entire base around it,” Green said. “Figuring out what your players are best at and how they learn to play their best is also a challenge.”

A 2024 study found that coaches who take time to build close connections with their players often see their athletes respond with greater focus and effort.

Researchers from the Department of Sport and Leisure Studies at Namseoul University revealed that players tend to thrive when their coach’s approach matches their own way of learning and competing.

Watching Green interact with his players during games, it’s clear he has high energy when he directs yelling and jumping at his players to get them excited.

“On the field, high energy, encouraging guys,” said Green about his personal coaching style.

“He always brings a lot of energy,” Aaron Nice, current football player for the Eagles, said. “In football, sometimes just being loud is what boosts energy.”

Nice said having a coach like Green, who recently was on the same path as him, makes it easier to connect.

While Green’s move from player to coach is a personal story, the shift from player to coach is not unique.

Staying with the game

A 2017 study found that nearly all professional football and rugby head coaches in England had previously played their sport at the elite level.

Researchers from The Taylor & Francis Group refer to this as the “fast-tracked” pathway.

Players are often promoted quickly into coaching positions without going through long formal programs because they’re seen as already having the right knowledge and credibility.

It’s a natural progression that keeps the sport’s culture alive and allows mentors like Green to pass on lessons such as discipline, teamwork, and resilience to the next group of young athletes.

Director of the Coaching Minor at Bridgewater College, Tammy Sheehy, creates classes for the minor, teaches classes, supervises students’ practicums, and knows about the athlete-to-coach transition all too well from past students.

“I had a former student who is now an assistant coach at a school getting ready to play Bridgewater and emailed me asking me to come watch her coach,” Sheehy said. “Moments like that are really cool to hear from students when they explain that they are doing well and they have continued on their journey to become a coach.

Sheehy said one of the biggest challenges she sees athletes face when making the transition is thinking the knowledge they know about the game means they are going to be a good coach.

“You need to learn the ways of coaching before you can actually teach and coach. Sheehy said. “A lot of athletes do naturally have it, particularly if they were leaders on their team.”

Green landed a coaching job straight out of college with no coaching experience. Turns out, this is not an unusual path for Division III athletes.

A 2020 research study by researchers at Bowling Green State University and Clemson University examined the difference between Division I athletes and Division III athletes transitioning out of sports.

Researchers Smith and Hardin found that many athletes in Division III see coaching as a natural next step in their lives. In contrast, they stated Division I athletes never let go of chasing the pro’s and put off what comes next.

What comes next

Green said he plans on taking an extra step in learning the best way to prepare for opponents during the week to put his athletes in better positions.

“You want to make sure your players are as prepared as possible,” said Green, “That’s the next step for me as a coach because it’s something that I can control.”

As Green gets deeper into his career, he hopes to learn how to develop his energetic coaching style into a more balanced style. “I can’t be so lost in screaming and yelling that I don’t see the scheme and what’s going on and being able to teach.”

Green’s journey reflects a growing trend among former athletes who transition from player to coach.

The shift requires more than knowledge of the game. It demands patience, adaptability, and a willingness to keep learning.

For Green and others following a similar path, the challenge lies in transforming passion into purpose and energy into leadership.