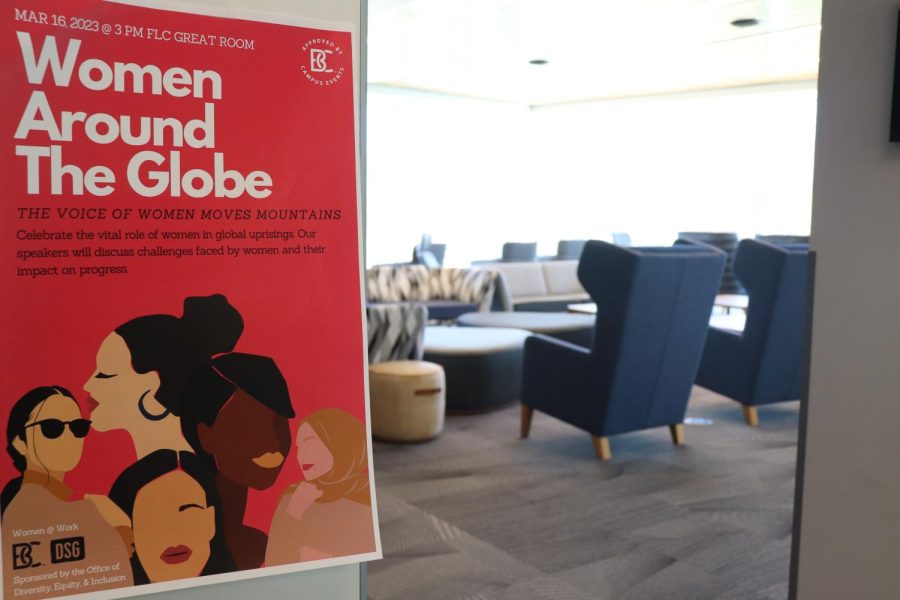

Women Around the Globe Roundtable Discussion

The Women around the Globe roundtable was held in the Forrer Learning Commons Great Room. Seating was arranged in a circle to simulate a round table environment and there were refreshments available.

March 21, 2023

Bridgewater, Va.-On March 18, the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and the Women At Work club held a Women around the Globe Roundtable Discussion led by Associate Dean of Students – Diversity and Inclusion Gauri Pitale, Associate Professor of Political Science Bobbi Gentry, senior Anton Kopti and senior Elizabeth Gaver. The discussion was open-ended and meant to take into account women’s experiences around the world.

“Going into Women’s History Month, I like to bring an international perspective,” said Kopti. “I personally wanted to bring a Middle Eastern perspective, specifically a Palestinian one, of women-led protest. Women face abuse from two different governments: their own and that of occupiers.”

The roundtable discussion began with introductions and segued into the topic of women in Palestine. Kopti explained the occurrence of “honor killing” in Palestine, a cause of femicide, as Kopti explained, to “preserve the family’s honor.”

Kopti introduced the story of Israa Ghrayeb, who was allegedly killed in the West Bank on Aug. 22, 2019.

“Palestinian women took to the streets to speak for themselves,” said Kopti. “People are equal when they attend a protest. Gender is overlooked.”

Kopti also discussed a more recent story: the murder of Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh in December 2022 by Israeli forces.

“The journalist was covering protests and was killed while wearing a press vest. She was a very prominent figure, and her death felt like a targeted act of silencing Palestinian women,” said Kopti. “Women are a big part of Palestinian and Middle Eastern resistance.”

Following this discussion, Pitale discussed the feminist movements in India, including dowry debts and female infanticide.

“Siring a son in India is a big deal. In the late 80s or early 90s, ultrasounds where you could tell the sex of the child began. We knew about female infanticide then, but there were so many lost female children when people knew the gender,” Pitale explained.

A study by the Lancet found that there were approximately 13.5 million missing female births between 1987 and 2016, with an increase of almost 60% between 1996 and 2007.

“Around the mid-18th century, the treatment of women was the worst we have seen historically. Something archaeologists will tell you is the minute society moved to farming culture, the status of women just tanked. We are still fighting these problems, but in modern times it is more like fighting to work and such,” said Pitale.

Pitale explained, however, that there are matriarchal communities in India.

“Early reforms began in the 19th century breaking down patriarchal systems within Indian communities. They aren’t all this way, but the majority are. There are actually some communities which are matriarchal or matrilineal, likely stemming from roots of the Shakti,” said Pitale.

Shaktism, or Saktism, is the worship of divine female power in South Asia, particularly the worship of the Hindu goddess Shakti. According to the Asia Society, It is believed that Shakti is the “dynamic energy that is responsible for creation, maintenance, and destruction of the universe.”

It is believed in Hindu tradition that women are vessels of Shakti, and therefore of both creative and destructive power. It is argued that Shaktism can either be utilized by the patriarchy to push women in Hindu communities to conform, otherwise they “are considered destructive, disrupting community and family social structures,” or it can be used to empower women.

“I like the ability for women to create gendered safe spaces for themselves in non-Western cultures. I find it interesting; women co-opting their repression to gain power, to gain privilege,” said Pitale.

Following the discussion of women in India, Gentry discussed her research on intersectional identities.

“Intersectionalism is how our different identities can inform politics, like race, gender, ethnicity, and how those things can be contradictory and how that can inform who we are and how we perform our politics. It also affects governmental recognition,” said Gentry.

In recent feminist movements, discussion of intersectional feminism have come into play, including discussion of past progress made and how early feminist progress was not always inclusive. Legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, who was discussed during the roundtable, is said to have coined the term “intersectionality.”

“In the [DeGraffenreid v. General Motors] court case, a Black woman sued the company because they wouldn’t hire her as a Black woman. The case was thrown out because the company claimed they did hire Black people,” said Pitale. “They realized the company only hired Black men as intensive labor and they only hired white women as administrative assistants. They did not hire her because she was Black plus a woman.”

Gentry described this rhetoric introduced during the rounding which utilizes “plus” between descriptions of identity.

“Intersectionality is the fact that people can be multidimensional. A piece of literature I once read says Black plus lesbian plus woman does not equal Black lesbian woman. We are not necessarily our identities summed, but that’s how we tend to measure it. The way we understand the world is from our different perspectives which can be both supportive and contradictory. It is a new field of study in sociology. It is revolutionary in political science,” said Gentry.

Gentry explained that the multi-dimensionality of humans means that one identity assumed by an individual may grant them a certain status which may contradict a status granted by a different identity.

The conversation moved forward in discussion of women in leadership.

“It’s hard to get into those spaces, keep those spaces and then create more of those spaces for other women,” said Pitale.

In response to this discussion, Gaver commented on places where there is a gender quota.

“Sometimes, people wonder, are women in these positions to fulfill a quota, or to be a symbol or are they there to actually make substantive change and promote women’s rights in their roles?” asked Gaver.

Despite representing 58.4% of the U.S. workforce, women only held 35% of senior leadership positions as of September 2022. Pitale argued that the normalization of women’s difficulties coming into positions of leadership further hinders progress.

“People say women just have to work twice as hard. Don’t normalize that. Don’t say that’s just how it is. Challenge that so it is not the same rhetoric for future generations. Be aware of privilege and see how to open up spaces for others,” said Pitale.

Kopti both began and closed the roundtable discussion with an Arabic proverb.

“The voice of a woman is a revolution,” said Kopti.