Pedagogy and Identity Across Academia in America, Bosnia and Malaysia

“Context Matters” in Teaching Approaches

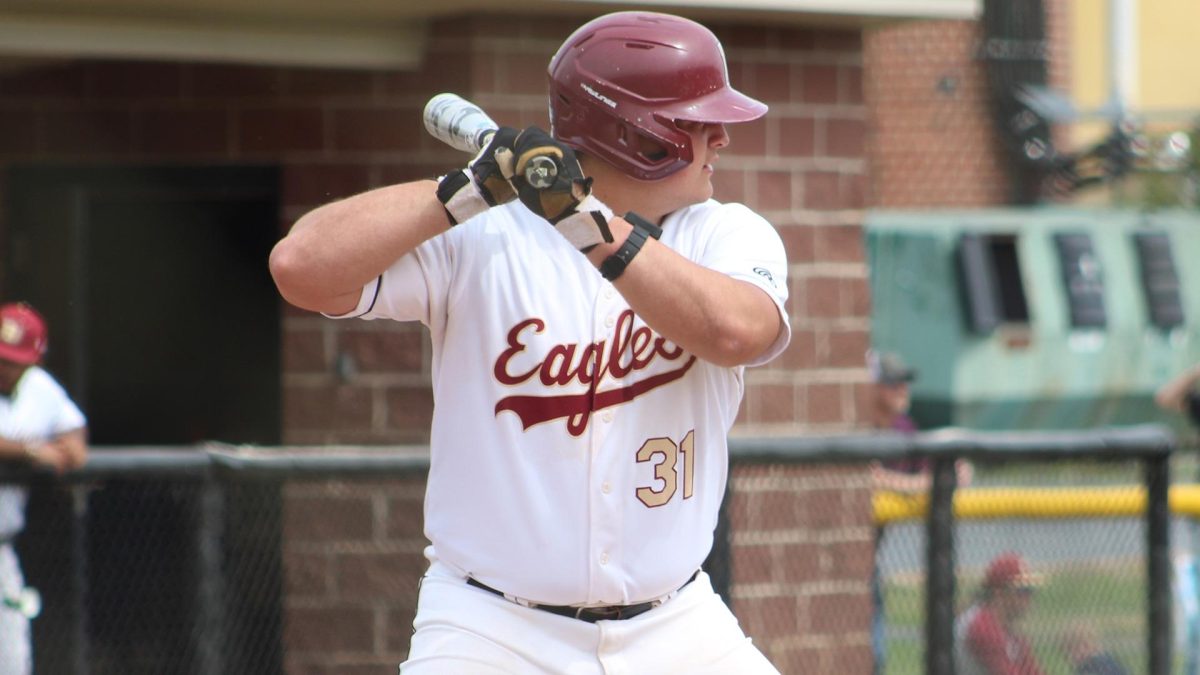

Bridgewater delegation outside of the Faculty of Islamic Studies at University of Sarajevo. From Left to Right: Junior Hunter Potts, Professors Harriet Hayes, Jamie Frueh and Nancy Klancher and sophomore McKenzie Melvin.

April 23, 2019

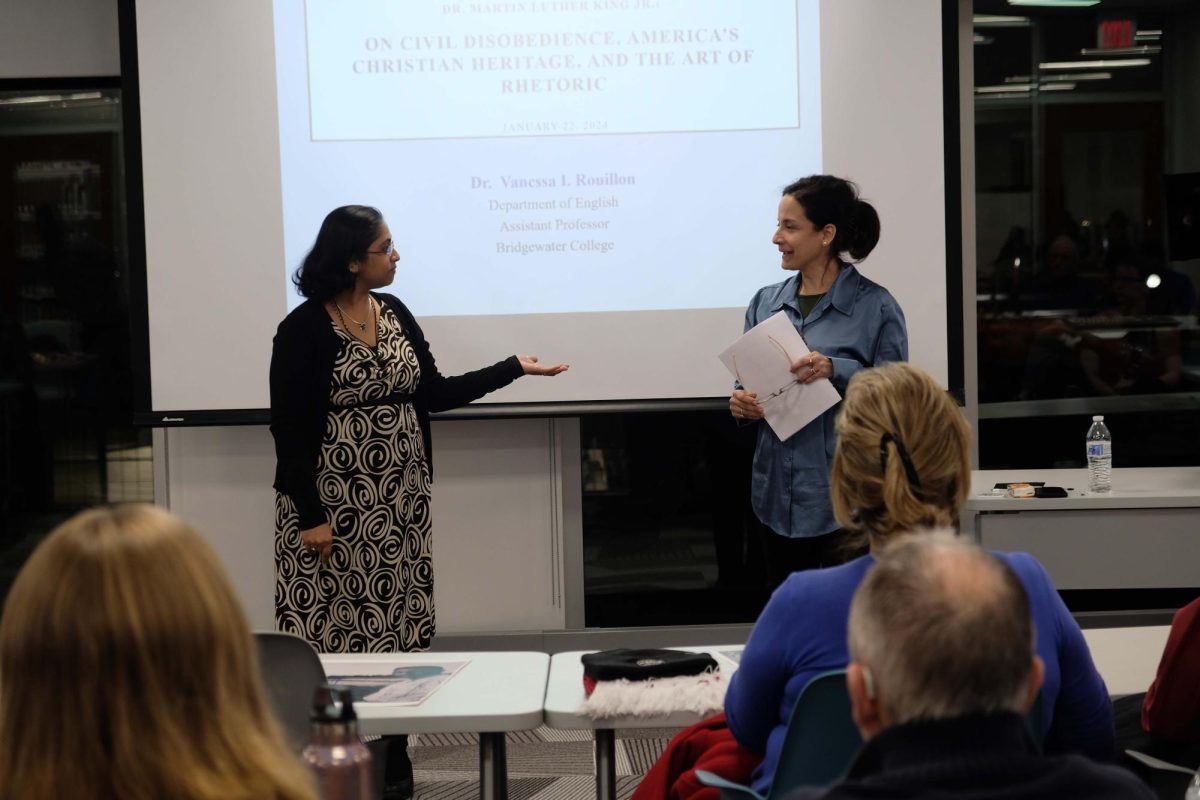

Bridgewater, Va.- Delegates from Bosnia and Malaysia visited Bridgewater February 2 to February 5 to observe classroom structure at Bridgewater College. Sophomore McKenzie Melvin and junior Hunter Potts also visited Sarajevo March 5 to March 9 and Malaysia March 10 to March 14 as part of the Barzinji Project. Harriet Hayes, Head of the Division of Humanities and Social Sciences, instructs the Sociology of Birth and Death course observed by the visiting faculty members and students. Across the American, Bosnian and Malaysian cultures, Melvin and Hayes found political context largely influences teaching styles and identity.

The Barzinji Project, according to Melvin, is “part of Shenandoah University’s new Center for Islam in the Contemporary World and is a completely grant-funded project with the intent of honoring the life of the late Dr. Jamal Barzinji [who] dedicated his life to international and transcultural collaboration.”

Potts stated he “got to experience the Bosnians’ ethnic divide–between Bosnians, Croats and Serbians–and how their history and wars still play into their politics currently and how that still really divides them now.”

The day of the classroom observation, Hayes explained the Sociology of Birth and Death class was discussing the topic of African American funerals in America. Student delegates from Bosnia and Malaysia were offered an invitation to participate in the discussion, but not required. Faculty were not included in this initial dialogue work among the students, Hayes said.

“For the students, this was the first time…they had been in a classroom that talked about death…but also where they were asked to share their own personal experiences,” Hayes stated. This was new to the visiting students and according to Hayes they expressed worry over participating in this new way.

Despite the experience being a first, the students ultimately participated, Hayes said, with Bridgewater College students also asking the students questions.

According to Hayes, a delegate from Bosnia asked Bridgewater students, “‘Do you think you actually learn this way?’”

A concern amongst the visitors was content mastery, Hayes said. There was a lot of discussion and connections made between students regarding personal accounts according to Hayes, which raised concerns over understanding facts of the reading.

Bridgewater students explained it is the student’s responsibility to come to class with the assigned readings completed. In the classroom, hearing other ideas and sorting through complexities is the core focus.

“They were critical of what looked like me not teaching because I wasn’t standing in front of the room,” Hayes explained. One delegate questioned why Hayes did not write on the board as the conversation progressed.

“That’s what I’m hoping the students do…I’m hoping the students begin to see how ideas are connected,” Hayes said.

Another delegate felt there was “no structure” when observing Hayes’ class. Hayes has noticed once she writes key points on the board, it often restricts students’ thinking and the conversation starts to shut down.

“It can be uncomfortable in my classroom if somebody wants a linear outline to get to point A to point B to point C,” Hayes stated.

“Because I’m a sociologist, I have this sense that there are cultural differences and peoples’ experiences frame and shape how they think about the world–their belief systems, their value systems…and the only way you get at those is if you start to unpack our assumptions about those things,” Hayes continued.

Melvin explained, “Islamization in higher education assumes that the problem of postcolonial (modern) knowledge is manifested in the social sciences and humanities…that the Western practice of using reason, rationalization and relativism to think about the world in the context of the social sciences and humanities has damaged, if not destroyed, knowledge.”

Educators often try to solve this problem through using the Qur’an, according to Melvin, who stated, “Islamization, properly understood, is inclusive of integration and harmonization and has nothing to do with attempts to convert others to Islam, or with political goals.”

Potts said Islamization interested him because “in America, we use more of a secular view,” whereas in Malaysia, “they’re trying to fit scientific knowledge or learned knowledge into the view of the Qur’an.”

“One of the things that this collaborative opportunity with the Barzingi Project is about is thinking about the overarching goals of higher education…I also think we’re preparing you to be active participants in your communities, active engaged people in the world…I’m preparing citizens,” Hayes explained.

Hayes said, “You have to figure out how you’re going to collaborate…as a professional you have got to be able to talk to people who are in another profession because ultimately there’s going to be a team of you trying to solve a problem.”

“On September 16, 2019, all delegates from all four universities [Bridgewater College, Shenandoah University, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the International Islamic University of Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur] will gather at Shenandoah University for a Fall Colloquium to present our findings and convince the Barzinji family that they should re-fund this experience,” said Melvin.